Demystifying Deep Learning: Part 10

Recurrent Neural Networks

September 17, 2018

6 min read

We move onto the next neural network architecture - the recurrent neural network, used for tasks where the input is a sequence.

Motivation

As with CNNs, it is worth first considering why we have this specialised architecture.

Our motivating example for sequence modelling is the task of sentiment analysis - given a movie review we want to classify it as positive or negative (binary classification). The notebook contains code to train a recurrent (LSTM) network to classify the sentiment.

How do we determine an overall sentiment?

For now, we can assume that each word can be mapped to an input vector (a word embedding) - we’ll cover this mapping in more detail in a later blog post.

Approach 1: Feed words individually

One approach is to feed each word to a feedforward neural network independently, and then average the probabilities. There is a key issue with this- the order of the words is lost.

Consider “good, not bad” and “bad, not good” - these phrases have two completely opposite meanings despite containing the same words.

Order matters - we want our neural network to use information from previous words when it classifies future words.

Approach 2: Feed words in a batch

So to get some idea of order, we could pass in a batch of words to the network at the same time - i.e. concatenate all the word vectors. However, given that a review may be 150 words long, and each word is represented (typically) by a 300 dimensional vector, we run into a similar problem as the CNN: too many parameters.

Moreover, the feedforward neural net requires a fixed-size input - this involves either padding the input to ensure it is the same length, or worse, clipping short a review so that it doesn’t exceed the input length.

Both approaches have their drawbacks, so we need to use a different architecture.

Recurrent Network Architecture

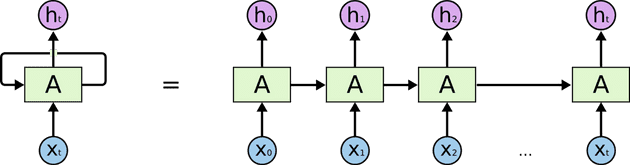

Rather than having the huge vector for a batch of words, we want to keep track of the effect of previous words in some sort of “memory”. We can do this by feeding in one word every timestep and then keep track of the output activation from the previous timestep and feed it back to the network (see above image).

Note that a given phrase could occur 50 words into the review or at the start and the effect on the sentiment would be the same. So noting this invariance across time,we can share weights across time - so inputs from all timesteps have the same weights.

This solves the issue of keeping track of prior information, whilst the recurrent loop also ensures we can input variable length sequences.

Notation:

Let’s define the notation we’ll be using when referring to RNNs, now that we need to keep track of the timestep:

is the value of the input at timestep , with and correspondingly the label and activation at time step . The length of the input, , is denoted by and likewise we have - note these may differ.

Based on the value of and we can split the tasks into 4 categories:

- Many-to-Many e.g. speech recognition, machine translation

- Many-to-One e.g. sentiment analysis

- One-to-many e.g. sentence/music generation given initial word/note

- One-to-One - this is the realm of standard feedforward networks

Forward Propagation:

Forward propagation consists of two steps at each timestep - compute the current activation ,given our previous activation and input , and if necessary the prediction given .

Just like with a feedforward neural network, this involves multiplying by a weight and adding a bias, and then applying some activation function .

We initialise (the initial activation) to a matrix of zeros of size x , where is the number of neurons in the RNN. Then for each timestep :

Typically for the activation functions, we use tanh when computing , whilst with this will depend on the task and loss function.

Note that is an x matrix, is an x matrix and that denotes a concatenation of the two matrices to form a x matrix.

So now we’ve got this new architecture, it seems we are good to go. However,there is one fundamental issue.

Backpropagation through Time

Consider the LSTM/ recurrent network architecture as an unrolled network, where each timestep feeds into the next. Each timestep can thus be viewed just like a layer in a standard feedforward neural network, so we backpropagate through each timestep from the end backwards (hence backpropagation through time).

Note that the weights in a recurrent network are shared across all timesteps, so we calculate the gradient with respect to the weights for each step and sum them across timesteps.

The Vanishing and Exploding Gradient Problem

If you think about an unrolled RNN, it is very deep - often a typical review for our sentiment analysis task will be 150-200 words long.

Since each layer involves the same operations, the effect of backpropagating the gradients through each timestep is compounded.

For intuition, let’s simplify the net effect of backpropagating the gradient through a timestep as multiplying the gradient by some value . So applying this operation times results in the gradient multiplied by .

If then this means that becomes larger and larger as increases - this is the exploding gradient problem. A simple fix for this is gradient clipping - for all values greater than a threshold, we just set the gradient to that threshold, so the max value the gradient can be is that threshold.

If then this means that gets smaller as we go further back through the network - so it means that the gradient for the first few words becomes almost non-existent - this is the vanishing gradient problem.

This happens to RNNs since the derivative of is

The vanishing gradient problem is an issue because it means the neural network can’t remember long-term dependencies - relating back to our motivating example of sentiment analysis, this means that the neural network may “forget” the first few words of the review, and thus only use the last few words in the review (the ones it has most recently seen) when classifying the review as positive or negative.

We want the network to remember the most important words, regardless of whether the model has seen it recently, or much earlier. This requires a modification to our RNN architecture.

The GRU Architecture

GRU (Gated Recurrent Unit) Networks modify the RNN as follows:

We want to have a more nuanced approach to our RNN, since certain words capture the overall meaning of the review better e.g. amazing, enjoyed, rubbish, boring , whereas some words don’t really add much e.g. the, a, and.

So at each timestep, instead of the one update operation, we have gates that control how much information is going into the GRU.

- Reset gate: how much of the previous activation to drop when generating our “candidate” for the next activation.

- Update gate: how much of the previous timestep’s activation should carry over to our current activation - how much of the past timesteps we wish to remember.

So intuitively, we’re controlling how much we want to remember/forget at each timestep - the gates give us finer control than just weighting the input and previous activations.

Maths:

For the reset and update gates, 0=don’t let through, 1=let completely through. We use the sigmoid function, which outputs a value between 0 and 1 to denote how much of that value we should let through. We store these reset/update gate values for each element in the hidden layer as x matrices respectively.

We denote our “candidate” for the next activation as - note how similar this is to the RNN equation - except we have our reset gate - note if this is roughly zero we have effectively reset the candidate value’s memory to include only information from the current timestep’s input. The reset gate thus quantifies how “relevant” the information from the previous timesteps is to this timestep.

The final activation is determined by our update gate - how much we want to update the activation with the current candidate versus how much we wish to carry over from the previous timestep’s activation.

The LSTM Architecture

(Note the image above uses h instead of a to denote activation of cell).

Whilst GRUs solve the vanishing gradient problem and are very effective, there is also another commonly used recurrent network architecture, which is the LSTM (Long Short Term Memory) architecture.

Just like the GRU, LSTM networks have gates, however the LSTM also contains a memory cell which is also a x matrix. There are 3 gates in an LSTM regulating the flow of information into and out of this memory cell:

- Input gate - how much of the candidate cell memory at this timestep do we want to store in the cell memory

- Forget gate - how much of the previous cell memory do we want to remember/forget in the next step (0=forget 1=remember).

- Output gate - how much of the current cell memory is relevant to the output activation.

The intuition is that the memory acts as a “information highway” in the cell, and that it helps store the long-term dependencies that the cell activation (the output) doesn’t store. So for example, if the network doesn’t need a previous piece of information in the current timestep but will need it in future timesteps, then its ouput gate value will be zero (so not part of the output activation), but its forget gate value will be 1 (so not forgotten).

Maths

The equations are thus as follows:

Firstly, the gates are just like the GRU gates - with their own weights and sigmoid activation function.

is the candidate for the new cell memory - note we don’t use a reset gate here:

Instead, we have independent gates for updating and forgetting (not tied to each other like and as in the GRU):

And finally we have the output gate:

Code:

def forward_step(a_prev, x, c_prev, parameters):n_a = a_prev.shape[0]input_concat = np.concatenate((a_prev, x),axis=0)IFO_gates = sigmoid(parameters["Wg"].dot(input_concat)+parameters["bg"])c_candidate = np.tanh(parameters["Wc"].dot(input_concat)+parameters["bc"])c_next = IFO_gates[:n_a]*c_candidate + IFO_gates[n_a:2*n_a]*c_preva_next = IFO_gates[2*n_a:]*np.tanh(c_next)cache = (a_next, c_next, input_concat, c_prev, c_candidate,IFO_gates)return a_next, c_next, cache

Conclusion:

The GRU and LSTM cells are the two main recurrent network units used in sequence tasks. The motivating example uses an LSTM network for sentiment analysis on a dataset of IMDB reviews, as an extension you could instead use the GRU and compare how it performs - the architectures are very similar to code up!

In the next post, we will look at deriving the backpropagation equation for the LSTM cell, and wrap up the series by looking at how this ties into backpropagation for any neural network architecture.